La Fiesta de la Toma stirs controversy over Spain’s Islamic heritage

by Emilio Alzueta

GRANADA

History can easily become a matter of names and definitions. The great Brazilian pedagogue Paulo Freire pointed out the relationship between naming and power: the winners of history, the powerful, coin the language that creates a vision of the world which will benefit their interests. Admittedly, there is always room for legitimate differences of opinion; yet, a classical epistemology -also upheld by the Islamic tradition- predicates the possibility of knowing reality as it is, of distinguishing truth from falsehood. Striving towards an adequate and truthful understanding of history, within its inevitable limitations, is a necessity which cannot be discarded by the allurement of ideological interests, nor by invoking a kind of exaggerated postmodernist perspectivism.

In 1492, the last Nasrid king of Granada -the only remaining territory of the great civilization of Al-Andalus- surrendered the city to Ferdinand and Isabel, the Catholic Kings who had unified the Christian kingdoms of the north into a single state. For them, as for so many others afterwards, this was the culmination of the ‘Reconquest’, a term that implies conquering back what had once existed, before being taken away. This notion has always underpinned a certain line of Spanish historiography which considers that the Romans and the Visigoths had formed an entity that could already be considered Spain, on the foundations of Roman law and Catholic Christianity -an entity which was then invaded and conquered by the Muslims, and which, notwithstanding the glory of their civilization, was understandably taken back and unified as a Christian country, pure in the true faith and in the eradication of unorthodoxy.

The great Spanish historian Américo Castro -and those that follow his seminal work- disagree,  however, with this assessment. According to them, there was no such thing as ‘Spain’,

however, with this assessment. According to them, there was no such thing as ‘Spain’,

which, as in the case of other European countries, was only formed in the Renaissance; and the Muslim heritage in the Iberian Peninsula, which lasted for eight centuries, is at least as much a part of Spanish history as that of the Romans or Visigoths. So there can be no Reconquest as such. Rather, the facts point to a Crusade, carried out not only by the Christian kingdoms of the north of the Peninsula, but by soldiers coming from other parts of Europe. The culmination of the so-called ‘Reconquest’, in 1492, coincides in time with the expulsion of the Jews from Spain –some of whom had lavishly financed Ferdinand and Isabel’s military campaign against Granada. And it also coincides with another powerful definition, that of the ‘discovery’ of America, which semantically justifies pillaging the wealth of the new continent, decimating the indigenous population and transforming Colombus’ journey into an epic voyage that erases those who had sailed there before, such as the explorers of the kingdom of Mali, in West Africa, at the beginning of the 14th century.

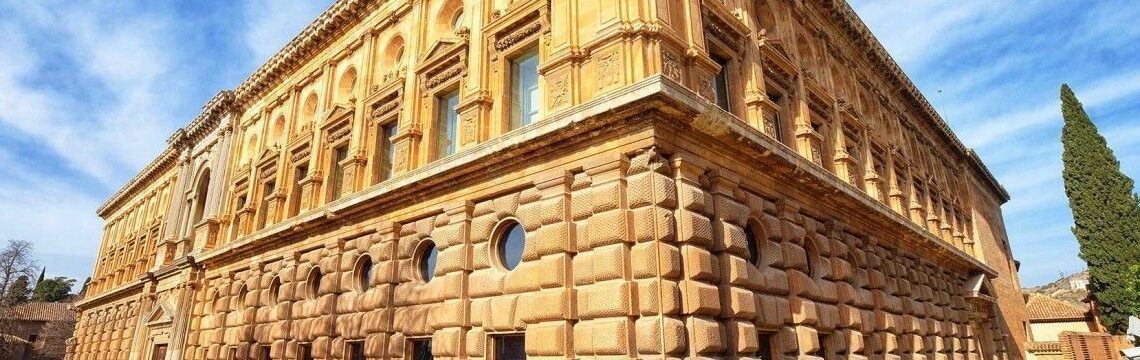

Every year on the 2nd of January, the city of Granada still witnesses La Fiesta de la Toma, the celebration of the conquest of the city by Ferdinand and Isabel, culminating in an offering at their graves in the cathedral, on the very site where the Nasrid mosque once stood. The fact that this festivity stirs up bitter controversy and protest has not stopped what many citizens of Granada consider a cherished tradition which, furthermore, symbolizes the unification of Spain and the magnanimity of the Catholic Kings; according to the current conservative major of Granada, verbatim, ‘with comradeship between the winners and the defeated’. But was this really the case?

When Boabdil surrendered the city of Granada to the Catholic Kings, he did so under the terms of the Treaty of Capitulation, which, among other assurances of liberal treatment, asserted that “the Moors will be entitled to keep their religion and their properties” and that “the Kings will only set up among them governors who treat the Moors with respect and love”. A mere ten years later, in 1502, when pressed by Cardinal Cisneros and the Inquisition, the Kings signed the decree by which all Muslims of the old kingdom of Granada -which was not restricted to what is now the province of that name in Spain- were confronted with two options: either forced conversion to Christianity or expulsion. As the latter usually involved Draconian caveats such as the abandoning of property and separation of families, as well as hazardous trips with serious risks to life and limb, most of the Muslims chose the first, hoping to be able to practice Christian rites in public while remaining Muslims in private. Hence they became Moriscos, or ‘Little Moors’. In the course of the following twenty years, the same fate would be met by the Mudéjares, the Muslims who were living in Christian lands, mostly in Valencia and Aragón, and whose excellence in agriculture and the crafts made them a cherished asset for the powerful landlords. The history of the Moriscos throughout the 16th century is one of extraordinary oppression and gradually increasing persecution at the hands of the Inquisition, as sanctified by the monarchy. Their crypto-practice of Islam was under a growingly stifling scrutiny, until in 1567 a decree (pragmática) of Philip II forbade, among other things, the use of the Arabic language -including the characteristic writing of Spanish in Arabic characters, called Aljamiado-, their traditional dresses and celebrations and the use of baths. This largely led to the mutiny of the Moriscos in the mountainous region of the Alpujarras, and then to a savage war in which the Spanish army massacred thousands. In 1609 a final decision was made under Philip III to forcefully expel the Moriscos from the kingdom of Spain. According to the most conservative historical calculations, about 300,000 Moriscos left the country, mostly from the ports of the region of Valencia. Some, especially in areas which were hard to access, managed to stay, and some even found a way to creep back, but the majority settled down in places like Morocco and the Ottoman vilayets of Túnez and Argel, where they would come to be known as Andalusies. Sultan Ahmet I issued letters encouraging princes to ease the journey of the Moriscos to their destinations, which included Istanbul, more precisely the Galata district, where there already existed a community of Muslims from Al-Andalus, as well as Sefardíes -Jews who had been earlier expelled from Spain, which they called Sefarad. In contrast with the millet system of the Ottomans and the convivencia of al-Andalus, Spain took the direction of the ‘purity of faith and blood’, which was the mark of a vision which would then plunge Europe into two centuries of intra-Christian religious wars, at the same time as establishing a new colonial definition of world geopolitics.

When Boabdil surrendered the city of Granada to the Catholic Kings, he did so under the terms of the Treaty of Capitulation, which, among other assurances of liberal treatment, asserted that “the Moors will be entitled to keep their religion and their properties” and that “the Kings will only set up among them governors who treat the Moors with respect and love”. A mere ten years later, in 1502, when pressed by Cardinal Cisneros and the Inquisition, the Kings signed the decree by which all Muslims of the old kingdom of Granada -which was not restricted to what is now the province of that name in Spain- were confronted with two options: either forced conversion to Christianity or expulsion. As the latter usually involved Draconian caveats such as the abandoning of property and separation of families, as well as hazardous trips with serious risks to life and limb, most of the Muslims chose the first, hoping to be able to practice Christian rites in public while remaining Muslims in private. Hence they became Moriscos, or ‘Little Moors’. In the course of the following twenty years, the same fate would be met by the Mudéjares, the Muslims who were living in Christian lands, mostly in Valencia and Aragón, and whose excellence in agriculture and the crafts made them a cherished asset for the powerful landlords. The history of the Moriscos throughout the 16th century is one of extraordinary oppression and gradually increasing persecution at the hands of the Inquisition, as sanctified by the monarchy. Their crypto-practice of Islam was under a growingly stifling scrutiny, until in 1567 a decree (pragmática) of Philip II forbade, among other things, the use of the Arabic language -including the characteristic writing of Spanish in Arabic characters, called Aljamiado-, their traditional dresses and celebrations and the use of baths. This largely led to the mutiny of the Moriscos in the mountainous region of the Alpujarras, and then to a savage war in which the Spanish army massacred thousands. In 1609 a final decision was made under Philip III to forcefully expel the Moriscos from the kingdom of Spain. According to the most conservative historical calculations, about 300,000 Moriscos left the country, mostly from the ports of the region of Valencia. Some, especially in areas which were hard to access, managed to stay, and some even found a way to creep back, but the majority settled down in places like Morocco and the Ottoman vilayets of Túnez and Argel, where they would come to be known as Andalusies. Sultan Ahmet I issued letters encouraging princes to ease the journey of the Moriscos to their destinations, which included Istanbul, more precisely the Galata district, where there already existed a community of Muslims from Al-Andalus, as well as Sefardíes -Jews who had been earlier expelled from Spain, which they called Sefarad. In contrast with the millet system of the Ottomans and the convivencia of al-Andalus, Spain took the direction of the ‘purity of faith and blood’, which was the mark of a vision which would then plunge Europe into two centuries of intra-Christian religious wars, at the same time as establishing a new colonial definition of world geopolitics.

When in October 2015 the Spanish government passed a law allowing dual citizenship for descendants of Sephardic Jews, globally estimated as around 90,000 – 4,307 of whom benefited almost immediately -, the initiative was partly presented as a kind of historical rectification. At a special ceremony held in Madrid’s Royal Palace, the Spanish king Felipe VI said it was “a privilege” to be able to write “a new page in history,” and saluted the Sephardic Jews with a welcoming “How we missed you!” From the very inception of the bill, more than one year before, there were many who questioned the obvious: why this difference of treatment between the descendants of the Jews and the Moriscos? The discrimination had already started more than two decades ago, when the first group were granted preferential status for obtaining Spanish nationality. The official response has stressed the conservation of the 16th century Spanish language -called Ladino- among some of the Sephardic Jews, but the fact is that, just as some of Jews had kept the keys to their ancestors’ old houses in Toledo or Gerona, the same can be said about the Andalusies in places such as Morocco: a sentimental symbol of connection that has remained as alive in families of both communities. Beyond any official justifications, some analysts have pointed out the economic benefits that such a law could bring from powerful Jewish lobbies, especially in America. In our modern democracies, the craft of naming is not so much an overt instrument of power but of subtle manipulation: public language remains very different from the true, hidden language of real politics.

While it is certainly true that the wrongs of history cannot be repaired, both private and public gestures of recognition can at least assuage the past with the balm of knowledge and acknowledgement. But they must be honest and fair. Beyond power and dissimulation, naming can also be an act of objectivity and compassion: the best guarantee that we may take from history the lessons we need in order not to repeat its evils.